Dead Mom Math

What was lost, what was gained, and who I became after losing my mom

We have to start with some Dead Mom Math.

My mom died one month after I turned 19.

At age 29, I had lived 10 years without her.

At age 39, the scale tipped: I had officially lived more of my life without her than with her.

I’m 42 now.

That’s 23 years without her.

She was 47 when she died.

If I also die at 47, my kids will be 13 and 7.

That’s only 5 years from now.

That thought takes my breath away.

*

For my entire adult life, I’ve seen the number 47 blaring ahead of me like a flashing neon sign.

47 flash 47 flash 47 flash.

If you’ve lost a parent young, you probably know this already—how an age can become a destination, a deadline, a question mark. You can’t help but wonder: is that number my fate too?

Every year I get older, she gets younger in my mind. A 47-year-old mother to a 19-year-old kid might as well be 64, or 80, or 3,002. Back then she was just “mom,” shapeless and uninteresting in the way parents are.

Now I can see it clearly: she was so goddamn young.

*

This is what I call my Dead Mom Math—the equations that have lived in my head for most of my life.

The subtraction, yes, but also the addition.

Because Dead Mom Math isn’t only numbers.

It’s the tally of what is lost: everything that isn’t here that could have been.

And, somehow, it’s also the tally of what is gained: everything that exists only because she died.

What might have been is always solve for X. An eternal equation with no set answer.

What’s the formula for my husband never meeting her? What are the numbers for my kids?

And then there is the other side of it: what have I gained from living most of my life without her? What choices, relationships, habits, ways of thinking, pieces of myself exist precisely because she died, and died so young?

And aren’t I glad for them?

How do you calculate that?

She would have been 70 years old today.

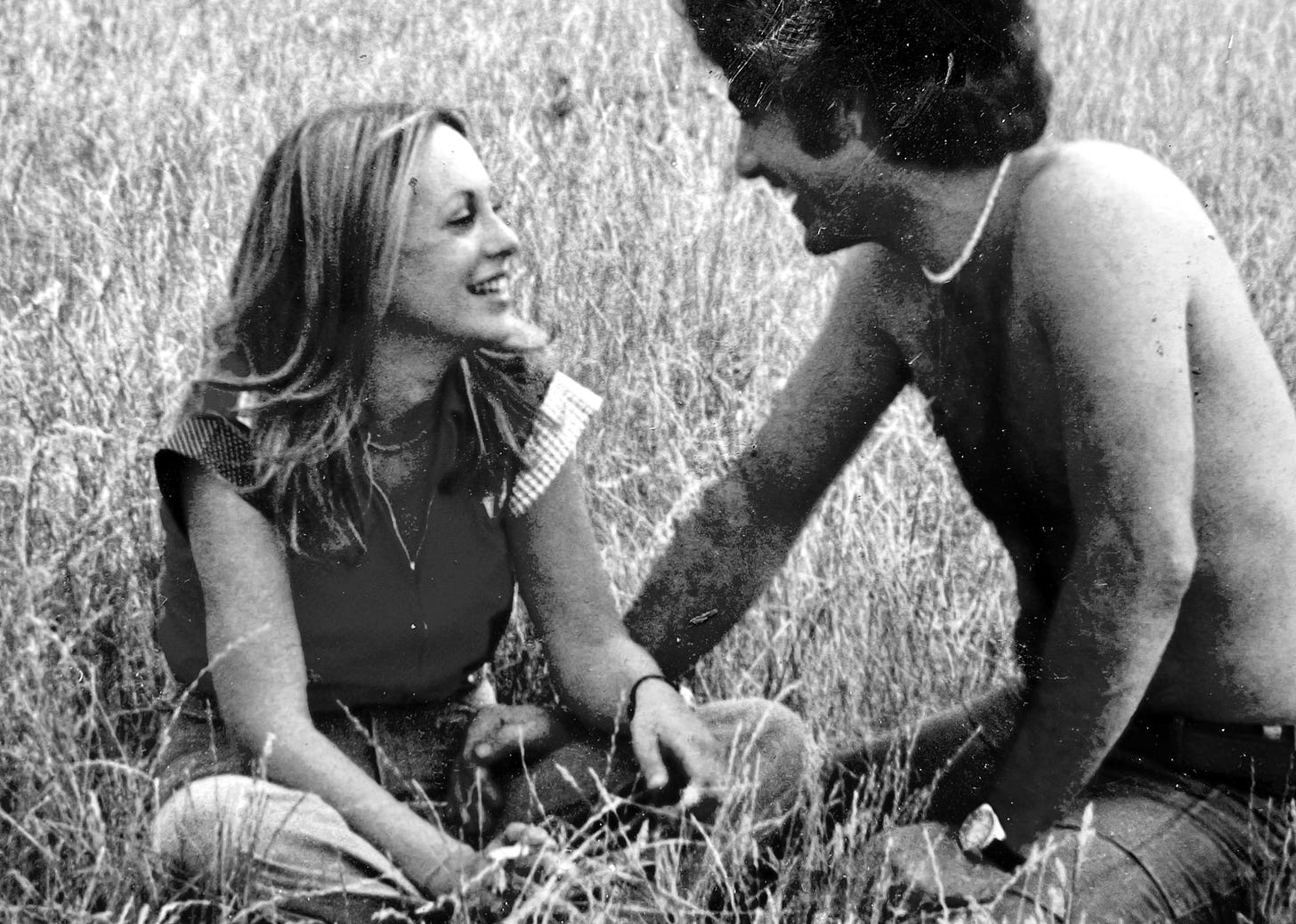

My mom and I had a complicated relationship, like many teenage girls and their mothers do.

When I think of her, I see her frozen in time in a snapshot from the late ’90s. She’s circling our neighborhood with tiny arm weights, doing Jazzercise and Tae-Bo routines in the living room, gabbing on the kitchen phone while the microwave nuked our dinners. Tie-dye T-shirts, bedazzled biker shorts, scrunchy socks, bright pink lipstick. Ricki Lake and Rosie O’Donnell on the TV. The O.J. trial. The 90s Knicks. Diet Coke and Shake ’n Bake. She’s dancing to the oldies station, suntanning unabashedly in our backyard.

All the trappings of a suburban mom in the ’90s. She played her role so perfectly.

To be honest, at the time she embarrassed me. Her happiness, her peppiness, that big, toothy smile. Everywhere we went she knew someone; she loved chatting and gossiping and yenta-ing for hours. My clearest image of her is this: a shake of her hair and hips, a sparkling, “How do I look?!” before going out. She was bright as the sun, completely radiant, and yet it repelled me. Or maybe it upset me by showing me what I was not.. or at least what I could not yet be.

I couldn’t touch it, whatever it was. I needed my wall up with her.

I was still an awkward, uncomfortable teenager, after all. Personality-wise, I took after my dad more. Slightly aloof, a little reserved, an observer who can turn on the charm when needed, but who would always prefer to be just outside of the circle than at the center of it.

My mom was all extrovert. I was a teenage tangle of angst and discomfort, hormones and self-consciousness, and I wanted nothing to do with any of it. I wanted nothing to do with her.

At that point she was still only the two-dimensional “mom” in my mind. A chauffeur, a buzzing nag in my ear. I couldn’t yet comprehend her as a full person with her own wants and fears and dreams. I caught glimpses of it—her sparkling laughter with friends, the way she danced in the living room with my dad, how she could command a room with humor and light, her face bright and shining—but then, just as quickly, my wall would rise again.

For years after she died, I tortured myself over the stupid things we fought about the year she was sick. Things like doing the dishes, my tone of voice, staying out too late. All the inane bullshit of daily teenage life. We didn’t know she was dying. We knew she was sick, but not dying. My head was so firmly up my own ass… which, developmentally, was probably exactly where it was supposed to be. I had finally escaped the suburban town that had always felt so suffocating to me. It was my freshman year of college and I was drunk on space and freedom and reinvention (and, honestly, a bit drunk in general).

I really wasn’t thinking much about her at all.

And then it felt like I got my wish, and I absolutely hated myself for it.

In the years after she died, I used to think that if my mom had just lived a little longer, we would have worked it all out. If she had only made it to my 25th birthday, I was certain we would have been best friends. Now, I’m not so sure. People have complicated relationships with their mothers their whole lives. There’s no guaranteed version of the story where she stayed alive and everything tied up neatly. I truly cannot say what would have happened between us.

What I do know is that every choice, every decision, every path I took in my life—especially in my early twenties, which set the stage for everything that came after—was made with her loss on my back. The tangle and weight of my grief informed me, for better and for worse.

Would I have drank and used drugs the way I did if she were still alive? Maybe, but probably not. And yet, if I hadn’t, I wouldn’t have gotten sober. I wouldn’t have rebuilt myself from the ground up. I might never have been able to meet and marry my husband, go back to school, build a career I care about, or have the children I have now.

Her death wrecked me, but it also made me.

I may never know what our relationship would or could have been if she had stayed alive, but I do know the version I actually lived:

I did my first fourth step when I was 27—eight years after my mom died and two years into sobriety. I remember lying in bed, reading Eat Pray Love, as a newly sober person tends to do. From what I remember, Elizabeth Gilbert writes about making amends to her ex-husband, even though he wouldn’t speak to her. She stands on top of an ashram in India and says every single thing she needs to say to him out loud, honestly and completely.

I immediately closed the book on my chest and spoke directly into the air above me: Mom, I’m so sorry I was unable to show up for you when you needed me. I’m so sorry I was too young and dumb to appreciate you when I still had you. I love you. I miss you. I’m sorry. I thank you.

Then I went to sleep.

A few days later, I was getting my nails done for a friend’s wedding when a text came through from a number I didn’t recognize.

It said: “Hi, I just talked to your mom. Even though things did not work out the way you wanted them to, she wants you to know she is so proud of you.”

My heart stopped. What the actual fuck?!

I called the number back immediately and left the most unhinged voicemail imaginable: Hi, hello, who are you? I think this was a wrong number but also exactly the right number. I needed that message. That message was for me even though it wasn’t sent for me. Does that make sense? Can we talk? Can you call me back?

They never did. I never heard from that number again.

I still fully believe it was my mom, reaching out to me through time and space, forgiving me, loosening the weight of regret just enough so I could keep going and keep growing.

So yes, my mom died when I was 19. But when I was 27, she texted me and freed me.

Then, when I was 28, I met my husband and told him this exact story on our very first date.

I try to keep my mom alive in my mind, in my heart, and in my stories. I try to pass her down to my children. I never feel like I do her justice, though. I only knew her for such a short time in the scheme of things, and my memories, hazy to begin with, have already started to fade.

I know she loved summer, sunshine, and the beach. I know she loved the Beatles. She loved to dance, go on girls’ trips with her friends, and watch old movies like Gone With the Wind, Grease, The Wizard of Oz, and beach blanket flicks like Gidget.

I, for whatever reason, remember her eating cubed slices of honeydew and cantaloupe. Such a strangely specific thing to remember.

So, in the summer, my kids and I eat juicy melon on the beach. We listen to the Beatles, and I tell them her favorite songs. I dance around to the oldies in our kitchen, just like she did in ours back then. I pass along what I can—through taste, through sound, through story. If a slice of melon or the song “Ticket to Ride” can spark even one small pulse of her memory in my boys years from now, then I’ve kept her alive just a little longer.

I think of her. I talk about her. I wear her jewelry and play her vinyl records with my kids.

And I say her name out loud:

Judith Diane Kroten Mussafi—simply Grandma Judi to my kids.

“Don’t forget,” she would say with a big smile, “it’s Judi with an i!”

In a life-is-very-funny twist, I now live on the same barrier island where she once spent her summers tanning under the sun. I look at the ocean and think of her. I see her in my children, in my family, in the life I am living now. She is never fully gone. She is always here, as long as I’m here, no matter how many years pass.

One of the biggest gifts her passing gave me is perspective.

I am intimate with death. I know it is real, permanent, and waiting for all of us. I did not get the opportunity to live even one day of my adult life without that knowledge seared into my very marrow. I know firsthand that death can take good, beautiful women out of this world unceremoniously.

I am not so much afraid of death as I am fiercely grateful to be alive.

I recently read and related to a quote from Rainer Maria Rilke:

Death is our friend because it brings us into absolute and passionate presence with all that is here, with all that is natural, with all that is love. Life always says Yes and No at once. Death, in its way, is the true Yea-sayer. It stands before eternity and says only Yes.

Quite often, I can be fully present with my children and with my life exactly as it is and find peace simply because I am here to experience it. Sitting on the same beach my mother walked, looking at the same ocean, I feel abundant and grounded. I can snap outside of the storylines and hot takes of our time. I am here, in the real world, with real people, on this beautiful planet. I woke up, I took a breath, and that is enough.

I am grateful for every wrinkle, every gray hair, every day I get to hug and kiss my kids, every victory and every frustration, because all of it means I am still alive.

And that, in the end, is the final sum of my Dead Mom Math: loss and love, subtraction and addition, absence and presence, grief and gratitude, all converging in the life I get to live.

All the pieces lost and found. All the years of darkness, and the years of light.

The impossible totals of a life taken way too soon, and of another life still being lived.

(For my mom, Judi. August 29, 1955 - September 23, 2002)

Your mom would be soooo proud of the beautiful human, wife, mother and (luckily for me) sister you are ❤️

Beautifully written and woven. Your Mom lives on in your words. 💛